In South Korea, some of the world's biggest food delivery firms are scrambling to surf an estimated $4 billion wave of new orders, in a boom triggered by the coronavirus pandemic.

Koreans had already developed such an appetite for meal deliveries that the country ranked third in the world last year for food order services, according to consultancy Euromonitor. Now, tough social distancing rules and work-from-home policies to counter the pandemic have fuelled explosive growth.

South Korea's food delivery market is expected to jump 40 per cent this year to around $15.4 billion from $11 billion in 2019, Euromonitor data showed, topped only by China and the US.

Surging coronavirus-era consumer demand has stoked orders, supported meal pricing and made the prospect of a career as a self-employed rider - earning more per hour than many other part-time jobs - an attractive option for many after the pandemic drove Korea's jobless rate to a 10-year high earlier this year.

Contractor jobs like delivery riders will keep growing in number amid the pandemic, predicted Kim Sung-hee, professor of labour studies at Korea University, highlighting the need for government scrutiny of "non-regular work".

"A lot of the contractor jobs, including riders, have minimal access to labour rights," Kim said, "they have no access to occupational health and safety insurance and no employment safety net."

Responding to the demand surge, Woowa Brothers, the operator of leading food delivery service Baedal Minjok, said it expanded its pool of motorbike delivery riders this summer by nearly 50 per cent from 2,100 previously. Smaller peer Barogo, which like Woowa Brothers doesn't disclose details of its financial performance - said it is recruiting 5,000 more, creating openings for some otherwise unlikely riders.

Among those is Chey Young-ah, a 37-year-old former art teacher in Seongnam, 20 km (12.43 miles) south of Seoul. After the pandemic forced classes at her day job to shut, she saw brisk delivery orders at a fried chicken restaurant where she worked part-time, opted to become a rider herself instead in mid-August.

"I feel lucky I found this field at a time when deliveries are booming," she said. "One of the merits of this job is that the entry barrier is low. They don't care whether you're a man or a woman, you don't need a job interview."

Chey, who already owned a motorbike, says she earned around 1.8 million won ($1,565.22) last month while working six to eight hours a day, seven days a week - already nine times the pay as an art instructor.

UK farm swaps milk for cow cuddles as floods and food prices take their toll

UK farm swaps milk for cow cuddles as floods and food prices take their toll

Two jailed for stealing $6 million golden toilet from Churchill's birthplace

Two jailed for stealing $6 million golden toilet from Churchill's birthplace

Mongolia's 'Dragon Prince' dinosaur was forerunner of T. rex

Mongolia's 'Dragon Prince' dinosaur was forerunner of T. rex

Labubu human-sized figure sells for over $150,000 at Beijing auction

Labubu human-sized figure sells for over $150,000 at Beijing auction

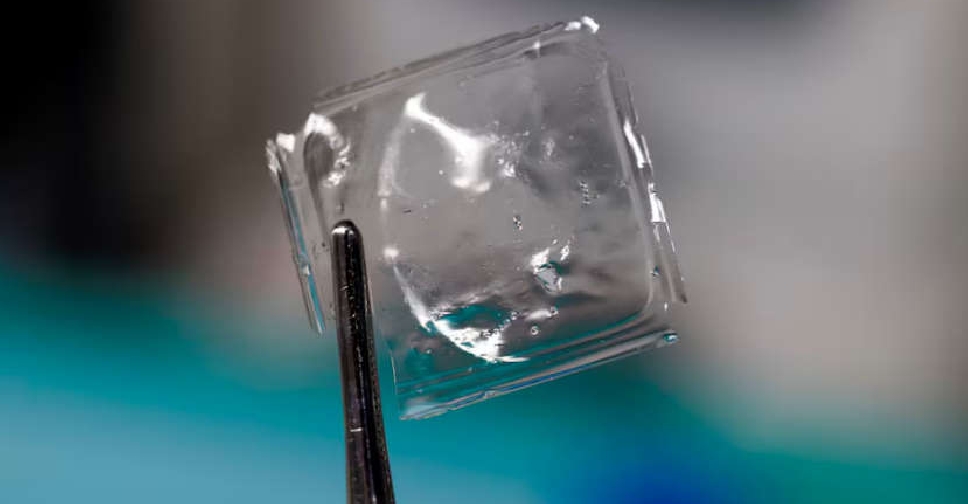

Scientists in Japan develop plastic that dissolves in seawater within hours

Scientists in Japan develop plastic that dissolves in seawater within hours